The Colombian folk songs that influenced Gabriel García Márquez’s ‘magical realism’

Gabriel García Márquez once described his novel “100 Years of Solitude” as a 350-page vallenato.

Vallenatos are mini-epics about characters from small towns, and the songs’ lyrics are filled with poetic imagery about local lore. García Márquez was such a fan of the music that helped create a Vallenato festival that still takes place every spring in the Colombian city of Valledupar. I visited this year to see if I could trace a connection between the music being played there today and the musical tradition that García Márquez so cherished.

You don’t have to look far for signs of García Márquez’s love of Vallenato in his work. It’s right there in his 2002 memoir, “Living to Tell the Tale.”

“I had dreamed about the good life,” he wrote, “going from fair to fair and singing with an accordion and a good voice, which always seemed to me to be the oldest and happiest way to tell a story.”

García Márquez would often mention Vallenato in his stories, even name-checking a beloved composer, Rafael Escalona. And he made Vallenato a central part of his most famous novel, “One Hundred Years of Solitude,”turning a real-life Vallenato accordionist, Francisco El Hombre, into a mythical balladeer.

“García Márquez took the real [Francisco El Hombre] and processed him through his ‘magical realism,'” Vallenato historian Tomas Darío Gutiérrez says. “The problem is when people confuse one thing with the other. And people think Vallenato began with ‘Francisco El Hombre’ taking an accordion, a drum and a ‘guacharaca’ instrument, and traveling all over the region, teaching the music he had invented.”

That origin story, Gutiérrez says, was invented by García Márquez.

It’s all part of the oral tradition that the novelist was steeped in, explains Raymond Williams, a professor at the University of California, Riverside who’s written extensively about García Márquez. Williams says García Márquez kept that tradition alive through the novel, and also through the annual Vallenato festival, where he was a regular.

“It’s a happy marriage for him literarily and eventually it became a real cultural marriage because he was famous for going to the Festival de Vallenato every year,” Williams says. “I guess until he became so, so famous that he just couldn’t do it comfortably anymore.”

Vallenato’s minstrel tradition is still very much alive at the festival. I saw some of it when I dropped in on a parranda in the city of Valledupar. These are small gatherings of friends and musicians who sing, tell stories, eat and drink Old Parr whisky.

The parranda I attended was hosted by the composer Deimer Marín. He sang and played guitar — no accordion. After a while, Carlos Mario Zabaleta, a well-known Vallenato singer arrived. And he told me a story: In October of 2006, while on tour in Mexico with the group Reyes Vallenatos de Colombia, he was invited to sing at a parranda hosted by the Colombian ambassador in Mexico City. The guest of honor was García Márquez.

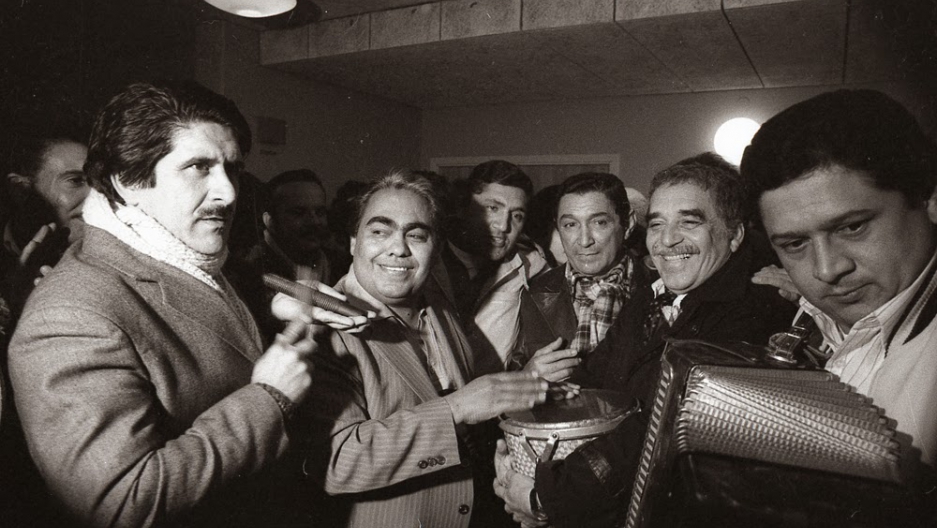

Zabaleta & García Márquez — with drummer Pablo López in the middle — after the Parranda in Mexico City

Credit: Lolita Acosta

“He started asking me about Armando Zabaleta, a great-uncle of mine, a Vallenato composer,” Zabaleta said. “You cannot imagine the nostalgia I saw in his face. I had no idea how long it had been since he last heard a drum, a guacharaca, an accordion. I will never forget that he asked me, ‘I would love for you to sing “La Diosa Coronada.”’ So when he died two years ago, I dusted off his books and re-read them, and I found the epigraph he included in ‘Love in the Time of Cholera,’ two verses from ‘La Diosa Coronada’: ‘The words I am about to express, they now have their own crowned goddess.'”

After he told the story, Zabaleta sang the song, and I cried.