From Ballrooms To Concert Halls, Mexico Kept This Cuban Style Alive

The Salón Los Angeles is the oldest dance hall in Mexico City. The classic 1930s ballroom is located in a working-class neighborhood near downtown, and every week, it sees dozens of well-dressed couples of all ages moving to an orchestra of saxophones, trumpets, trombones, clarinets and percussion instruments.

The music is called danzón, and it was born in Cuba in the late 1800s. By early in the next century, it had couples gliding in set patterns in a kind of formal square dance. It was huge. But, like popular music in every era, danzón was eventually replaced by more modern styles.

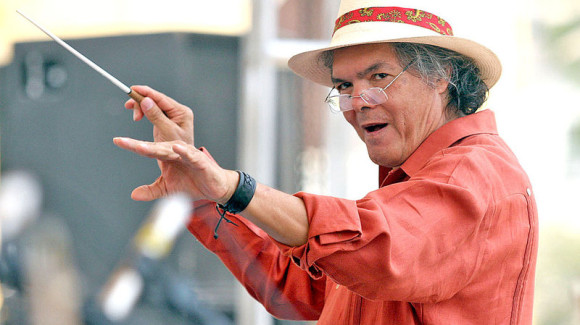

In Mexico, however, danzón is still a popular ballroom dance in cities across the country. Composer Arturo Márquez caught the danzón bug when he started going to a Mexico City dance hall in the early 1990s.

“And that’s where I really learned — the way they play, the danzón sounds, the rhythms, the melodies, more or less the harmonies,” Márquez says. “And especially the connection between the dance and the music, which is very strong. I think it’s one of the dances that the dance, the music, really goes together, all the time. It’s like a marriage.”

This kind of music and dance atmosphere inspired Márquez to compose not one, but a series of eight danzónes for orchestra.

“It allowed me to go into the symphonic world, into the classical world — I wouldn’t say easily, but with a very natural sense,” Márquez says.

Arturo Márquez was born in the northern state of Sonora. The family eventually moved to Los Angeles, where Márquez took up violin and later piano in high school. He eventually received a Fulbright scholarship to study composition with Morton Subotnick and James Newton at the California Institute of the Arts. But Márquez did not follow their musical path, says Aurelio Tello, a Peruvian composer and researcher based in Mexico City.

“Marquez signed the new epoch in music in Mexico because he refused the avant-garde style,” Tello says. “When he gave to know the Danzón No. 2, the avant-garde style was finished.”

Tello has written extensively about classical music in Latin America, as well as about Márquez’s work. He says when Danzón No. 2 premiered in 1994 in Mexico City, the audience reaction was intense.

“The audience was shouting, and for five or six minutes, the audience were clapping,” Tello says. “It was amazing. I don’t remember, never, in 30 years, 32 years that I’m living in Mexico, a similar occasion, a similar perception, a similar situation. The public was impressed with danzón.”

Danzón No. 2 has been performed by orchestras around the world. Superstar Venezuelan conductor Gustavo Dudamel, who leads the Los Angeles Philharmonic, makes Márquez’s music a regular part of his concerts.

Márquez wrote Danzón No. 2 in early 1994. But he wasn’t trying to conjure a bygone era so much as respond to the social and political upheaval around him, particularly the Zapatista Chiapas uprising against the Mexican government.

“The social life around you really influences you, no? So that’s what happened inDanzón No. 2,” Márquez says. “Yes, there was this background, this knowledge background in 1993, of the salons, the dance saloons. But there was also this — what’s happening in Mexico in January and February, and I think this piece, it shows — it has hope. I think it’s a piece for hope, para esperanza.”

It’s music with echoes in an old dance hall and on the streets of Mexico today — musical paths Arturo Márquez will continue to follow into the future.